The Invisible Caravan

The Forgotten Participants

of the Spanish Invasion

of Inka Peru (1533)

It is recommended that you view this animation in Chrome or Safari. Recent versions of Explorer work too. Unfortunately, at the moment, images do not render correctly in Firefox.

To advance press →, ↓, or [space bar]. To retreat, press ← or ↑.

Introduction

1. This experimental visualization re-animates the 'invisible caravan' of the thousands of Indigenous and African men, women, and children that marched with Francisco Pizarro and his band of conquistadors on their famous march from Cajamarca to Cusco in 1533.

2. Spanish accounts typically only mention the 300 - 500 Spaniards that participated in this journey. They refer only obliquely to the Indigenous guides, spies, messengers, armies, laborers, and porters that assisted them throughout the journey. They make no allusion whatsoever to their numbers.

3. Later Indigenous sources provide fragmentary evidence of this assistance. For example, between 1558 and 1561, leaders of the large central Andean province of the Wankas petitioned the colonial court in Lima, detailing the assistance their predecessors provided to the Spanish invaders in 1533. However, even they make no mention of the many other groups that traveled with the conquistadors.

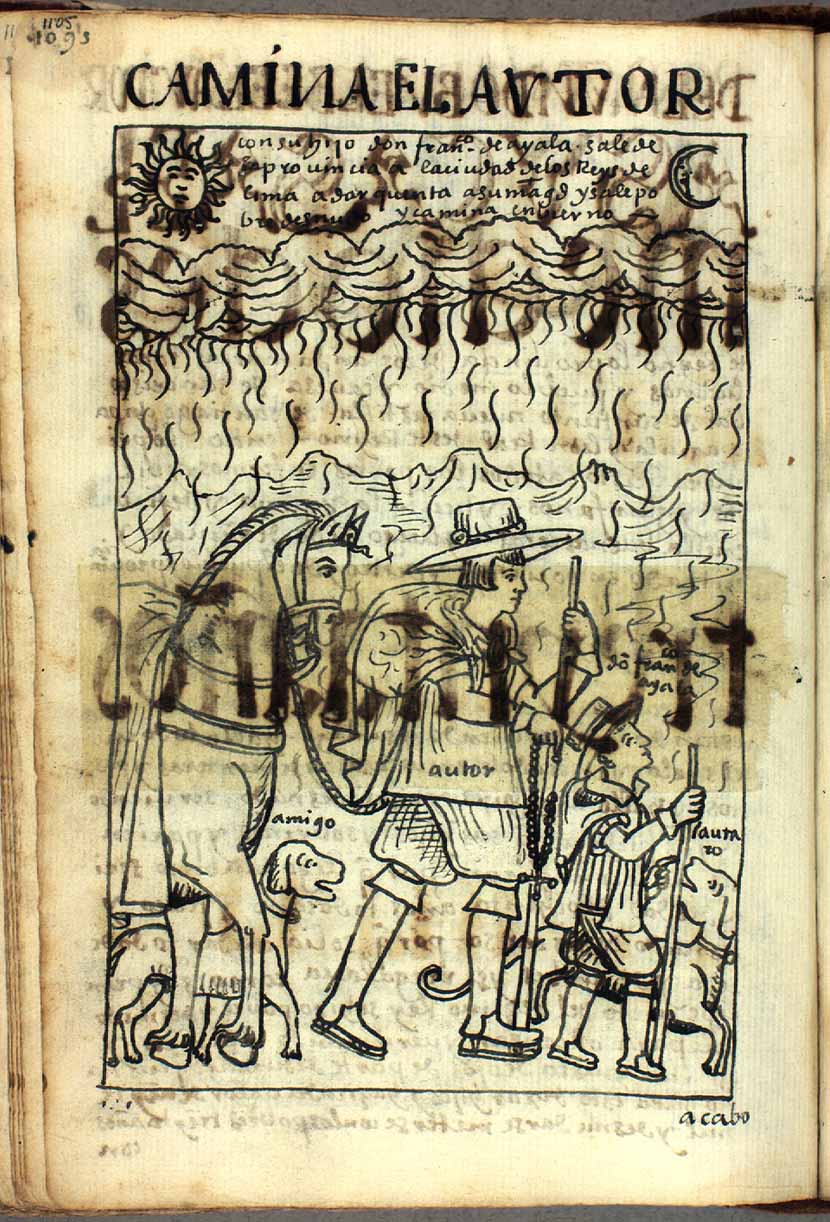

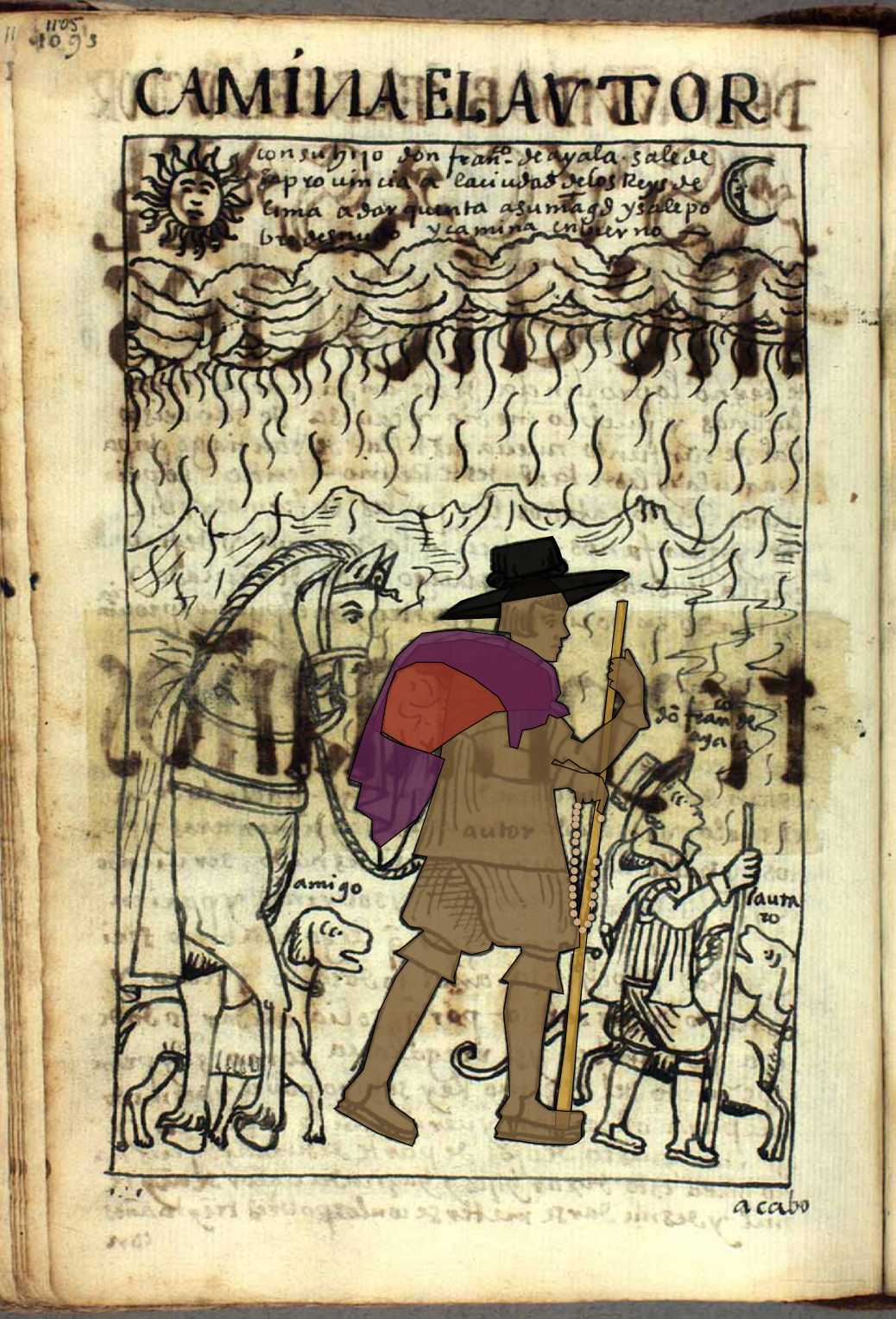

4. The artwork used here to illustrate the caravan was created by Guaman Poma over 400 years ago. As an elderly Andean man, Guaman Poma addressed a 1000+ page chronicle, full of hundreds of images, to King Philip III of Spain in the early seventeenth century. It is not known if the King ever read Guaman Poma's chronicle. We are listening now, however. His chronicle might be the longest, most detailed written criticism of European colonization ever offered by an Indigenous person during the early modern era (1500-1800 CE).

5. Assisting me in tracing Guaman Poma's figures was my daughter Raeka.

The integration of the resulting silhouettes with textual annotations draws inspiration from modern infographics and narrative cartography. However, it also draws inspiration from Guaman Poma himself, whose innovative combination of image and text was designed "to delight the King's eye as it educated his heart and mind."2

2. Valerie Fraser, "The Artistry of Guaman Poma," RES 29/30 (1996), 285.

The multi-ethnic caravan departed from Cajamarca headed south on August 11, 1533. To Francisco Pizarro's secretary, Pedro Sancho, only one person mattered. As he narrates, “the Governor [Pizarro] set out one Monday morning [Aug 11, 1533]” and later: “the Governor set out from that place.”3

3. Sancho, Ch. 3.

Approximately 300 to 500 Spaniards traveled with Pizarro.4

Images presented here represent a one-tenth sample of the estimated total size of the caravan. Thus, the 210 horsemen and 90 foot soldiers known to have participated in the expedition are represented by a total of 30 silhouettes traced from Guaman Poma's chronicle.

4. Although Sancho provides no totals, a review of the numbers he provides for different groups that split up during the course of the journey suggests 300 Spaniards, 210 with horses, participated in the expedition. Following Sancho, Edmundo Guillén Guillén argues Tupaq Wallpa departed from Cajamarca with “more or less 300 Spaniards.” Guillén Guillén, Los incas y el inicio de la guerra de reconquista, vol. 1, 517. Meanwhile, Juan José Vega argues that “no less than” 400 Spaniards traveled in the “offensive” of Pizarro and Tupaq Wallpa. Vega argues that Spanish authors also omitted lower-level Spanish servants. Los incas frente a España: las guerras de la resistencia, 1531-1544 (Lima: Peisa, 1992), 144.

but they were not alone. Traveling with them were...

Tupaq Wallpa, the newly crowned Inka emperor and...

the feared Inka general, Challku Chima, who marched with the caravan as a prisoner of Pizarro and Tupaq Wallpa, under the watchful eyes of some guards.5 Spanish eyewitness accounts do not mention any other Andean participants by name.

Besides the several hundred Spaniards and these two prominent Inka figures, who else traveled with the caravan?

5. Pedro Pizarro, Relación del descubrimiento y conquista de los reinos del Perú (Lima: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2013), Ch. 13.

If not for historians' relatively recent (re-)discovery of colonial-era petitions written by Andean communities, we would know little about the many Andean allies that traveled with the caravan. Reconstructing their presence and contributions requires scouring these petitions for fleeting references to the conquest period and reading traditional sources against the grain - identifying what they marginalized. Calculating the logistical demands of such a cross-country journey and contextualizing events within longer-term Inka and Andean history also aids such a reconstruction.

For example, Inka history suggests royal heirs would have never traveled alone. Upon arrival in Cajamarca, Tupaq Wallpa kept a low profile and hid with Pizarro to avoid capture by Pizarro's people. However, by the time of his coronation, he would have traveled with his own entourage and a sizable army, while being carried aloft on a litter wherever he went.6

6. Cieza de León alleges that both Tupaq Wallpa and the prisoner Challku Chima were carried on litters when the caravan departed from Cajamarca. Cieza de León, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Ch. 56.

Indigenous Women - A Double Invisibility

Andean women often suffered from a double invisibility. Rarely mentioned by Spanish authors, they were also regularly omitted in Indigenous texts and testimony recorded within a colonial system that ignored women. Yet, we know Quispe Sisa traveled with the expedition for the first half of the journey. As a ñusta, or daughter of the Sapa Inka, she served as an important intermediary that could negotiate and act on behalf of three different groups: the Spaniards, Inkas, and her mother’s province of Hanan Huaylas.

Despite Quispe Sisa's prominence and importance, only one historical source records her participation in the 1533 expedition: her own testimony recorded in Wanka petitions from 1560.7

7. Testimony of Quispe Sisa [Inés Yupanqui] in: Guacra Paucar, “Información” (1560), 254.

Other prominent Inka women were also present. Most notably, Kusi Rimay Ocllo - the coya or principal wife of Atawallpa - walked with the caravan. She did so, apparently against her will. An agent of the deceased Atawallpa covertly followed the caravan for several days, seeking, but failing, to liberate her.8

8. Betanzos, Narrative of the Incas, Part 2, Ch. 26.

Meanwhile, various provincial kurakas and ambassadors traveled alongside the Spaniards. Perhaps most prominently, they included representatives of the provinces of Chachapoyas and Wankas. These provincial groups provided porters to carry the caravan’s baggage and traveled with militias of their own, ready to fight the Inka resistance.9

9. Most Spanish accounts do not mention the presence of any Andeans on this journey besides Tupaq Wallpa and Challku Chima. However, in one notable exception, some conquistadors wrote from Jauja the following year, describing how they had set out for Jauja (not Cusco) with Tupaq Wallpa and “many other lords and principals.” Ayuntamiento de Xauxa, “Carta a Su Magestad” (1534), 117.

Besides the large Inka entourage that marched alongside the Spaniards, various figures traveled ahead gathering information and preparing the way. Most histories of the 1533 invasion depict the conquistadors as leading the vanguard of an imperial and intercontinental invasion. However, in a literal and figurative sense, they were not leading.

Andean provincial kurakas and various agents, spies, and messengers of the new Sapa Inka traveled in advance of the caravan, some hundreds of kilometers ahead.10

Tupaq Wallpa's spies

For instance, the newly crowned Inka emperor, Tupaq Wallpa, sent spies ahead to scout the position of the armies of the Inka opposition.11

11. Pedro Sancho frequently describes Pizarro receiving messages and news throughout the three-month trek from Cajamarca to Cusco. He never once mentions who delivered these messages so quickly and frequently: chaskis working under the direction of Pizarro’s Inka and Andean allies. Sancho, Account, Ch. 3. Inka spies, assassins, conspirators, rumormongers, and other secret agents flicker in and out of Inka histories just enough to reveal their existence but not long enough to indicate their identities or the nature of their experiences. In a fascinating historical novel, Rafael Dumett reconstructs the post-contact period from the perspective of an Inka spy. El espía del inca (Lima: Lluvia Editores, 2018).

Inka royal "repair[ing] the bridges and bad spots on the road"

In addition, a member of the Cusco Inka royalty traveled ahead of the caravan to "repair the bridges and bad spots in the road." Before the caravan departed from Cajamarca, this royal official, Wari Tito, offered to go to Cusco to prepare the way for the Spaniards. He then asked for and received a sword for his defense. The conquistadors would later learn Wari Tito was killed on the road by Atawallpa’s army.12

12. For Wari Tito’s arrival to the Spanish camp see: Cabello Balboa, Historia del Peru , Ch. 23. For Wari Tito effort to “protect” (*amparar*) Pizarro and his subsequent march toward Cusco see: Pedro Pizarro, Relación, Ch. 9, p. 57. Pedro Pizarro states that a “Guamantito” and a brother of his, Mayta Yupanque requested Francisco Pizarro’s permission to go to Cusco and that both were killed in the endeavor. This Guaman Tito was undoubtedly Wari Tito. Pedro Sancho describes Wari Tito traveling ahead of the conquistadors preparing the way and his subsequent death: Sancho, Account, Ch. 3, p. 10.

Guacra Páucar, kuraka of the Hurin Wankas

Also traveling ahead was a kuraka of one of the three large and powerful polities of the Wankas. Roughly half a year earlier, the kuraka of the Hurin Wankas, Guacra Páucar, had come to Cajamarca seeking an alliance with the invaders. With him, he brought gold, silver, royal Inka cloth (cumbi), blankets, llamas, and maize to offer to the conquistadors as gifts of alliance. Following Andean custom, he expected such gifts to be reciprocated just as he expected the 715 men and women he provided the Spaniards to be returned. Guacra Páucar then traveled ahead of the Spaniards to gather supplies and people to support their advance.13

13. Guacra Paucar and Guacra Paucar, “Memorias de los auxilios proporcionados" (1558), 201–10. Andean witnesses disagree whether it was Pizarro or the captive Atawallpa that compelled Guacra Páucar’s journey ahead.

Thus, Andean lords like Guacra Páucar and Inka royal agents like Wari Tito prepared the way for the caravan’s advance. Scouts, spies, and messengers also kept the expedition’s leaders informed.

Chaskis running like 'sparrow-hawks'

For generations, runner-messengers known as chaskis had been relaying messages for the Inkas across the difficult terrain of the Andes. These chaskis, whom Guaman Poma described as running like 'sparrow-hawks', quickly covered the distance between relay stations placed at intervals of approximately one to eight kilometers across the Andes. Through this relay system, ethnohistorical sources indicate chaskis could transport messages up to 250 or 300km per day.14

14. Guaman Poma describes the capacity of these chaskis to run like “sparrow-hawks.” Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica,337 [339]; The sixteenth-century administrator Polo de Ondegardo describes these chaskis covering fifty leagues or approximately 250km per day; Similarly, Francisco de Jerez [Xerez] recalls Atawallpa saying the chaski system could relay a message from Cajamarca to Cusco (approx. 1500km) in just five days. Polo de Ondegardo, “Relación de los fundamentos,” 188-95 in El orden del Inca por el Licenciado Polo Ondegardo, ed. Andrés Chirinos Rivera and Martha Zegarra Leyva (Lima: Editorial Commentarios, 2013); Xerez, Verdadera relación, 107.

Both Spanish and Indigenous sources describe the constant exchange of messages between various actors, Andean and Spanish, near and far. They rarely mention, however, the chaskis tasked with relaying and delivering these messages.

Dogs (often mastiffs)

I have not found direct evidence that the conquistadors brought dogs with them in 1533. However, they were notorious for setting dogs on Indigenous people during earlier campaigns in the Caribbean and Mesoamerica. Similarly, eyewitness testimony in a 1541 case accused Francisco Pizarro's brother, Hernando, of burning Andeans and setting dogs on them to pressure them to produce more gold and silver during his campaigns of the 1530s.15

15. Hernando Pizarro did not march with the 1533 caravan. In this case, a rival conquistador describes in detail the many ways Hernando used torture to force Indigenous people to comply with his wishes, including setting dogs on them. “Información hecha ante la Justicia de la Ciudad de los Reyes a pedimento del Governador Don Diego de Almagro sobre la tirania hecha por el Marques Don Francisco Pizarro ya difunto” (Lima, 1541), Patronato,90a,n.1,r.11, AGI, Interrogatorio of 1537-04-20, bloque 3, Question 8, image 323?? and Interrogatorio of ???, bloque 3, Question 10, folio 76v.

Besides the messengers and spies running ahead and the regal assemblies marching alongside, long lines of people marched behind the conquistadors.

Although only rarely mentioned in the historical record, at least some of the provincial lords traveling with the caravan brought militias with them.16 Under the Inkas, it was common for provincial militias to serve imperial campaigns for a few months at a time.

16. The caravan received additional military assistance on the road. The Aymaraes, for example, provided a battalion to defend the Spaniards as they made their final approach to Cusco. Guachaca, “Información” (1668).

Meanwhile, trudging behind the Inka royalty, Spanish conquistadors, and Andean militias, was a long line of porters, servants, and slaves. Some porters were provided by Andean allies like Guacra Páucar and the Wankas, who expected their people returned.

Although llamas were regularly employed to carry baggage long distances across the Andes, much of the supplies of large armies on the move were commonly carried on the backs of human porters.

Under the Inkas, porters were usually replaced at the boundaries of each province. Thus, each province's Inka governors or regional lords (kurakas) were responsible for providing porters to assist armies and other state functionaries passing through.

In contrast to these accounts of willing allies, many others had been forcefully enlisted to assist the caravan’s advance. Many suffered terribly during such expeditions.17

17. In trial testimony, conquistadors often accused each other of the types of crimes they would never admit to otherwise. For example, in a 1537 case, various conquistadors accused Hernando Pizarro, Francisco’s brother, of allowing his countrymen to seize gold, silver, alpacas/llamas, and Andean women and children without paying. The witnesses also accused Hernando and his men of enchaining porters together by the neck, and cutting off the heads of any that faltered to avoid having to stop the human train to untie and remove stragglers. Perhaps most disturbingly, they accused Hernando of allowing his men to enlist new mothers as porters and rip their newborns from their breasts, killing them in front of the women, all so that their progress not be delayed. “Quaderno de Ynformaciones hechas por el Adelantado Diego de Almagro contra Hernando de Pizarro” (información, Lima, 1537), AGI Patronato,90a,n.1,r.11, bloque 3. The interrogation of these witnesses begins on folio 74. Questions 6-9.

Not a single historical source recorded any estimates of the total size of this caravan.

However, compiling different types of fragmentary evidence suggests that the total caravan likely exceeded 10,000 people. Such a caravan would have taken half a day to cross narrow bridges or traverse narrow passes.18 This evidence includes:

18. Military caravans numbering well in excess of 10,000 were common in the Inka period. In March 1533 - while Pizarro and most conquistadors remained in Cajamarca - a Black man returned from an exploratory expedition to the south, including an encounter with a large Inka army under the leadership of Challku Chima. The man reported that a khipu kamayuq (khipu-keeper) shared with him his count of the army's size he kept in his khipu (knotted-cord) registry; it indicated that 35,000 Andeans traveled with the army. The archaeologist, Terance D'Altroy, estimated that such an army would have taken thirty-seven hours of continuous travel to pass single-file over a narrow mountain pass or bridge. D’Altroy, Provincial Power in the Inka Empire, 86.

1. The Wankas testified to providing approximately 7000 warriors, porters, and servants during the course of the journey.

2. It would have required one thousand porters or more just to carry the gold and silver the conquistadors transported from Cajamarca to Cusco.

3. Various Andean witnesses indicate that tens of thousands of Andeans transported this gold and silver and other supplies and gifts to Cajamarca in 1532 and 33. As only a small fraction of this treasure was sent back to Spain from Cajamarca, the rest would have been transported to Cusco, requiring similarly immense baggage trains.

4. Other ethnohistorical evidence describes the passage of armies (and their camp followers) - in earlier and later campaigns - numbering in the tens of thousands.

African slaves appear sparsely in the historical record. Before returning to Peru from Spain in 1529, Francisco Pizarro received a royal license to take fifty enslaved Africans from Cape Verde to Peru as his own. Several other conquistadors received license to take one or two African slaves each.19

19. Not all African members of the expedition were slaves. For example, Pizarro awarded a portion of the gold and silver plundered from Atawallpa to Miguel Ruiz, a mulatto, and Juan García, a Black man.

One witness recalled 40 or 50,000 Andeans being captured in Cajamarca after Atawallpa's capture. Pizarro allowed his men to take whom they wanted for their service while the rest were sent back to their lands. Another witness recalled:

“They killed a huge quantity of Indians and imprisoned the said Atabalipa [Atawallpa] and stole a great quantity of gold, silver, cloth, alpacas, and Indian (both men and women) servants. Each Spaniard present took for himself a very great quantity, so much that, as he was going without restraint), there was a Spaniard that had 200 male and female Indian servants.”20

20. Molina, “Conquista y poblacion del Peru o destruccion del Peru,” 114.

In a letter from Panama, written in October 1533, a colonial official lamented the loss of 10,000 “indios” from Panama who were taken to Peru.21 However, given the small size and number of ships that had sailed from Peru to Panama prior to that date, this number is almost certainly exaggerated.

21. Letter: Lic. Espinosa al Emperador (Panama, Oct 10, 1533) in Porras Barrenechea, Cartas del Perú, Letter 52.

Llama caravans helped carry the baggage of pre and post-contact military campaigns in the Andes. One early report described 10,000 llamas filing behind Atawallpa in 1532, carrying food and supplies.22

21. Letter: Lic. Espinosa al Emperador (Panama, July 21, 1533) in Porras Barrenechea, Cartas del Perú, Letter 46.

In all, I estimate 10,000 or more people (Andean, Central American, and African; enslaved and free) traveled with the conquistadors. Although the slaves may have had no choice, many Andeans participated in the conquest expedition as allies to serve their own ends (such as the reconquest of their homelands). Tupaq Wallpa traveled near the front of this caravan, with a large entourage.

Thank you for visiting. To return to Shadowy Figures click here. To re-start, press the right arrow.

I created this presentation using the free, open-source presentaton platform impress.js, which was created by Bartek Szopka and Henrick Ringo.